-Department of English-

Health Humanities Undergraduate Research

Purpose

Art is an inherently humanistic endeavor. Be it on a screen or on a canvas, art is the oldest means by which we are able to express, empathize, and appreciate. In exploring the connections between the Visual Arts and Medicine, we therefore aim to do the following: (1) share and establish a comprehensive database of artwork and film for student use; (2) delineate the historical relationships between the 'doctor' and the 'patient,' between 'medicine' and 'society,' through study of this media; and (3) understand how the image of the human body has been represented over time.

Art as an Atlas

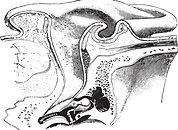

First, we shall examine the visual arts' most obvious use in the context of medicine: as an atlas. Medical textbooks in particular are replete with drawings of skeletal structures and muscle systems. This type of art is educational; this type of art must be accurate. It is meant to be sketched with an almost rigid, scientific stiffness-- the depiction of a human body, rather than the human body.

Film suffers from a similar recourse. Movies or videos that are at all to do with medicine are generally almost entirely educational. Public health campaigns by

the National Institutes of Health, for example, offer a historical glimpse

into a study of body and disease that is abstracted from the person. To paraphrase Andrew Solomon, they are stories of disease, not stories of people with

disease.

Here is a film from 1966 on Chagas' disease:

Source: National Institutes of Health

Notice the ways in which the disease is being described and "shown" here. How is art used as an atlas? How is it not? (See Exercises)

.

.

.

There are clearly two means by which we can view art in this way. It can be a literal atlas-- a guide to the body by accurate depiction-- or a metaphorical one-- a guide to the soul. The human body.

Let us now examine this latter sort of art: pieces that provide not just an atlas to the body, but an atlas to the soul; that vary from the artificiality we see above.

Take a glance at Tchelitchew's "Interior Landscape," where the essence of being and mind shine out amongst the tangle of veins and arteries. Or examine Ferguson's "Art and Anatomy: Drawings," depicting the curving imperfection of her scoliosis. This is a different type of art, an art which connects and humanizes, which tries to remove itself from the clinical austerity that medicine oft exudes. It is an atlas of another kind.

Now watch this film clip from "Wit" (2001) below:

Source: YouTube

"Wit" is, I believe, a very good example of disease trajectory as it is experienced rather than as it is taught or studied in medical textbooks. We see Emma Thompson's character, Vivian, undergo the trials and tribulations that come with an ovarian cancer diagnosis: she struggles to decide between treatments, faces an outlook that seems increasingly dark, and still tries, through it all, to find hope. The popsicles in this scene are a symbol for how we can choose to empathize with people outside of their being a "patient," to connect without all the clinical definitions that follow.

A rather clear juxtaposition from the NIH documentary. Indeed here, instead of a detached and objective view of disease, we get a very personal and subjective one. We are quite literally shifting perspectives, going from the physician-- training as they are to understand the intricacies and details of an illness-- to the patient-- also in a sense training to understand the intricacies and details of what is happening to their body.

.

.

.

It is important to note that in contrasting these forms of art, I don't aim to give one kind a higher value or worth. They are each meant for separate things, for separate purposes. But one must realize, I think, that at the end of the day they are also each meant to educate. Art as a visual map of the body tells us the more obvious, physical facts of our existence, while art in the more abstract-- in the works of Ferguson or in "Wit"-- shows us what it means to have a human body. They are each atlases, the latter perhaps more elusive than the former.

And it is because of this abstract art's less tangible meaning that I imagine many future projects and research will choose to focus on it. So, to prepare future investigators for this work, we will analyze and interpret primarily 'abstract' medical art in the Exercises found below.

Art and Society

Art can also tell us about society at large, about the ways in which we perceive medicine and all that it entails. What is, for example, our archetype of the doctor? Our view of the "typical" patient? Is their relationship that of a benevolent figure philanthropically caring for injured souls? Or is the physician a God-like individual: clinically dictating and stifling the humanity out of powerless people?

Historically, there have been many interpretations. I find art from nineteenth-century England to be especially revealing--rife as it was with "quacks" and painfully ineffective medical treatments. Let's examine some such paintings from the period below.

Source: UVA Claude Moore Health Sciences Library

Entitled "Gentle Emetic," this caricature by James Gillray was published in the year 1804. "Emetics" were, at the time, a popular medicine that induced puking, which was thought to cleanse the body of impure chemicals and humors. In this drawing, the patient and the physician are waiting for the emetic to take effect.

Notice in particular their faces. The doctor's placid, sympathetic gaze is a harsh juxtaposition to the pinched discomfort of the patient. Clearly, the "gentle" in the title is meant as a wry jab: this is decidedly not a pleasant procedure.

Gillray's etching offers a humorous commentary upon the so-called "heroics" of medicine. It gives us a glimpse into how English society often ridiculed medical practice and medical professionals of the time. The physician is here a confident fool, impressing their "treatments" unto the tired, surrendered recipient.

Another piece by James Gillray, "Metallic Tractors" was published three years earlier, in 1801. In this work, the focus is shifted to the "quacks" and charlatans that at the time pervaded the medical field; it particularly gives reference to 'metallic tractors' that they often used to cure rhinophyma, a medical condition that involved the enlargement and reddening of the nose.

Two things should stand out immediately in this image. The first is the bottle of brandy on the table next to the patient. Alcohol consumption is known to enhance the effects of rhinophyma, so the notion that it was right next to the medical practitioner-- right next to the "quack"-- emphasizes how out-of-touch these individuals were with real medicine. The second thing of note here is the shape of this man's hair-- it sticks straight out almost as if it were a devil's tail. This implies a hidden evil to the quack's agenda, that apart from the generally humorous connotation of this etching, there is a darker side to these sort of illegitimate practices.

Source: UVA Claude Moore Health Sciences Library

So, if the "quack" is the devil, does this mean the doctor must necessarily be the angel? It's difficult to tell in Gillray's work. There is certainly a difference in how each is depicted-- the physician's soft and benevolent face hardly compares to the strict and austere façade of the "quack." But their practices were both undoubtedly very painful and very ineffective. What then separates the two, in the public's eye?

I believe that this art tells us that we (or 19th century English society, rather) have an inherent trust in medicine. Doctors for the most part were compassionate figures who tried to use all the science that was available to them, limited though it might have be. Quacks disregarded science, and were thus made worse in our view.

Equally interesting to this is what the art teaches us about physician-patient relationships of the time. Despite the doctor indeed being more trustworthy than the quack, there was still a notion of doubt; you could still question and joke about historical medicine's occasionally nonsensical methods (for what really is a gentle emetic?) and gain public commiseration. That is something we don't see much of nowadays-- the complexity and evolution of medicine has distanced itself from common-sense understanding. It is much harder for the layperson to have and state an opinion (though doubtless they try all the same).

.

.

.

So, what does modern art tell us about society's perception of medicine? Certainly that it is, as aforementioned, much more complicated. But how does this translate to the doctor-patient relationship?

Watch these clips from "Wit" (yes, again!) and "Lorenzo's Oil" (1992):

Here we find more explicit examples of doctor-patient communication. In these two diagnosis scenes, a physician delivers troubling medical news-- in "Wit", it is the discovery of a woman's ovarian cancer; in "Lorenzo's Oil," that of a young boy's adrenoleukodystrophy, a disease relatively unknown.

As you watch these clips, notice the way in which the doctor speaks to the patient. In "Wit," the oncologist goes on a long, uninterrupted spiel about cancer treatments, only briefly pausing to see if Emma Thompson's character, Vivian, is following along. It is clear that she is overwhelmed, but he continues on nonetheless, suggesting a lack of empathy, a lack of understanding, on his part. In "Lorenzo's Oil," it is the parents of the patient that meet with the physician. The doctor attempts to explain to them that this illness is incurable-- which is true--- but it comes off also as harsh and unsentimental. Indeed, the physicians in these two movies both feel almost like the archetypal villain: the mad scientist who, with his advanced knowledge, has distanced himself from humanity. There is an obvious barrier between the patient and physician in these scenes, as if they are each talking at each other rather that with each other.

It seems therefore that modern movies-- and perhaps subsequently then modern society-- holds a view of doctors that is rather clinically austere. The gap of knowledge between the physician and their patient is rapidly increasing in today's world, and suggests the doctor-patient relationship is growing to be imbalanced, the doctor being supreme in their complex understanding of the body.